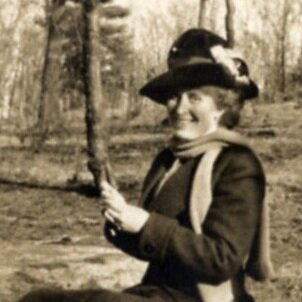

Ethel Paine (1872-1954)

Descended from a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Ethel Paine was one of the fortunate few of wealth and privilege to fully embrace social democracy. She was an outspoken pacifist and progressive, generously supporting international peace and social justice for workers, African Americans and women. Her circle of friends included Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, theologian Reinhold Neibuhr, Doctor Grace Walcott, and Hilda Proctor, a great-grand-niece of Harriet Tubman and secretary to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

As a young woman, Ethel was protected from the wider world as if she were a child. 19th-century women of all backgrounds were financially and legally dependent upon men, deprived of higher education, confined to the home and excluded from world affairs that could corrupt their innocence. Like children, they had no vote.

Volunteer work for the church and charitable organizations were exceptions to the rule. Considered natural guardians of society by nature of their sex, unmarried and childless women like Ethel could acceptably turn to social work.

She was deeply influenced by the Rev. Phillips Brooks of Trinity Church, a close family friend and leading intellectual of the 19th century, whose democratic theology of Christian Humanism guided her life work. In her teens and twenties, she was immersed in the St. Andrews mission of Brooks’ Trinity Church which served the diverse residents of Boston’s West End. The mission’s most innovative contribution was its women's medical dispensary run by Ethel's close friend, Dr. Grace Walcott, at a time when female physicians were rare. Vincent Memorial women’s health center in Boston (now a part of Massachusetts General Hospital) was the first to be open late on weeknights to accommodate the schedules of working women from as many as twenty-one countries and four continents.

Ethel’s mission experiences were formative, so much so that she made up her mind to live “among the people” at the Denison Settlement House in the South End, near workers’ housing, workers’ institutes and working girls’ clubs founded and funded by her family. However, a niece convinced her “to stay with us because even though the little foreign children might need her, her family and friends needed her still more.”

Keeping the peace with her prestigious family, Ethel lived for at time with Dr. Grace Walcott in Heath, Massachusetts, where her sanitarium offered “active cures” for women as healthy alternatives to the notoriously destructive “rest cures” prescribed by male physicians. Ethel bought a farm in Heath, which became the vibrant center of a growing colony of intellectuals like Frankfurter and Neibuhr.

Despite her progressive track record on women’s issues, Ethel was conspicuously quiet on women’s suffrage. Her “chief and greatest light” Phillips Brooks was pro-suffrage but both of her parents had been opposed to it during her childhood. As the president of the American Peace Society in the 1890s-1900s, her influential father worked with female leaders of both the peace and suffrage movements who predicted that “women as voters will become the peacemakers of the world.” In 1896, his conversion to women’s suffrage made national women’s news.

Only after her child bearing years did Ethel Paine opt to marry. In 1918, at age 46, she wed a kindred spirit John Moors, who described himself as a “friend of suffrage and peace and democracy.” A banker and philanthropist, Moors headed relief efforts after the San Francisco Earthquake, the Halifax Munitions Explosion and other major turn-of-the-century disasters, and served on the boards of Harvard and Radcliffe.

With her husband’s encouragement, Ethel became increasingly vocal about her political views. Friends from this part of her life remember her as a “fiercely radical progressive.”

She was a Christian pacifist and board member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, an interfaith peace organization founded in the US in 1916 to promote active nonviolence. When the US government investigated her like-minded friends in the clergy and higher education at the end of World War I, she publicly defended them for having “sacrificed high positions in order to be true to their convictions at a time when heated political opinion condemned freedom of thought and even the right to serve God ‘in their own way.’”

After the War, the Fellowship of Reconciliation expanded its mission to work for labor rights and an end to racism. She was one of six (along with AJ Muste) in the Comradship of the FOR which helped arbitrate the Lawrence Textile Strike of 1919. In the view of the Comradship, law enforcement, not the strikers, was the “creator of violence” in the streets.

Beyond peace and labor, Ethel Paine was an avid and generous supporter of equal rights for African Americans throughout her long life. She was a board member of historically black colleges Hampton Institute and Penn School; founded the Urban League of Boston with her husband in 1919; and funded an early speech of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “On the Threshold of Integration,” when others would not.

On her 80th birthday, Ethel Paine Moors married Rev. Charles Raven, chaplain to the Queen of England, and died on her honeymoon in 1954.

Waltham residence: 577 Beaver St. (now 100 Robert Treat Paine Dr.,) (Summers, 1872-1954)

Banner photo: Students of Hampton Institute, from Ethel Paine’s photo album, 1903. Stonehurst Archives.

Blackwell, Henry B. “Woman Suffrage Means Peace,” Women’s Journal, May 16, 1896, p 156.

Dillistone, F.W. Charles Raven: Naturalist, Historian and Theologian. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1975.

The interview with Howard Kester regarding Ethel Paine’s funding of the MLK, Jr. speech is available on line. Interview with Howard Kester, August 25, 1974. Interview B-0007-2. Southern Oral History Program Collection (34007). Martin Luther King, Jr.'s speech was republished as “At the Threshold of Integration,” Economic Justice 25 (June-July 1957)

Landstrom, Ada, Pearl and Ruth. “Memories of Ethel Lyman Paine Moors,” Heath Herald, vol 29, no. 2, July/July 2007, pp. 9-10.

Moors, Ethel Paine, letter to the Editor, Boston Herald, Jan 28, 1919, p. 10

Morice, Linda C. Flora White: In the Vanguard of Gender Equity. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017’

Paine, Sarah Cushing. Paine Ancestry. Privately printed, 1910.

Penn School Papers, Saint Helena Island, SC

“NY Women May Share in $4 Million Estate,” Jet, April 29, 1954.

Sifton, Elisabeth. The Serenity Prayer: Faith and Politics in Times of Peace and War. New York: WW Norton & Co., 2003.

Storer, Emily Lyman. “Happy Memories of a Much Loved Aunt by her Oldest Niece,” Mar 24, 1952. Stonehurst Archives.

Stonehurst Curator Ann Clifford wrote this biographical sketch in conjunction with “Anxious to Vote: Students, Workers and the Fight for Women’s Suffrage,” a curriculum and public education project developed in partnership by Stonehurst the Robert Treat Paine Estate and Waltham Public Schools in commemoration of the national suffrage centennial in 2020. STONEHURST is a National Historic Landmark owned by the City of Waltham. The once-private estate of generous social justice advocates whose ancestors helped establish the democratic foundations of this country is now appropriately owned by the people.

The Friends of Stonehurst received support for this program through “The Vote: A Statewide Conversation about Voting Rights,” a special initiative of Mass Humanities that includes organizations around the state.

This program is funded in part by Mass Humanities, which receives support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and is an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.