IDA ANNAH RYAN (1873-1950)

Ida Annah Ryan was the first American woman to earn a master’s degree in architecture and was the senior partner in one of the earliest all-women architectural firms in the country: Ryan and Luscomb. Despite her undergraduate and graduate degrees from MIT and her receipt of the prestigious MIT Rotch Travelling Scholarship, she was denied admission to the American Institute of Architects three times. She was also denied a department head position in local government purely on account of her sex.

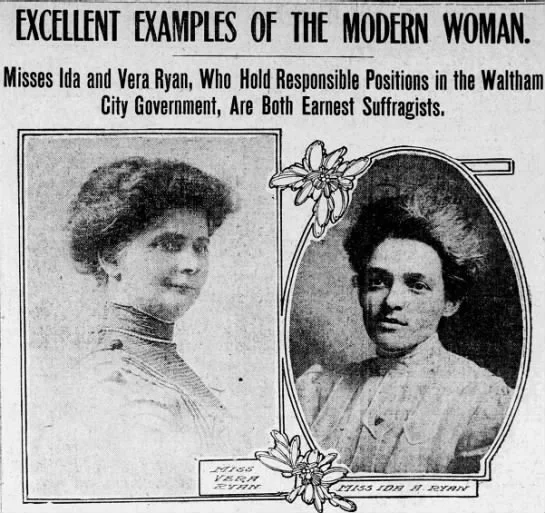

Ida Annah Ryan, Boston Globe, 1913

Ida Ryan was one of the leading professional women in Waltham and a local women’s suffragist. Of all women fighting for the vote, Ryan had the closest ties to Waltham, with roots here going back several generations. She lived and worked in Waltham for nearly five decades, and focused her activism locally on financial and political equality for women.

Despite significant setbacks, Ryan persevered in a field dominated by privileged men and became an accomplished architect. She is best known for her work in Florida after 1920, her early work in Massachusetts deserving further study. She was a mentor to fellow MIT graduate Florence Luscomb, who had been turned away from eleven male architectural firms in a single summer. Not only did Ryan welcome Luscomb as a partner in her practice, she encouraged her to take summers off to work for women’s suffrage. Florence Luscomb would ultimately leave architecture to become an influential political activist.

One particularly turbulent year in Ryan’s long and steady career in the City of Waltham Building Department drew public attention to women in senior government appointive positions typically monopolized by men. The goal she shared with Waltham’s pro-suffrage mayor was simple: for women to “be legally recognized as possessing qualities of mind that justify her in demanding to be placed on the same plane as men.” (Waltham Evening News, 17 March 1913)

By Ryan’s own account, both her mother Carrie and grandmother Mary were suffragists. Her earliest years were spent with her extended family living on her grandmother’s dairy farm on Lexington Street. Mary Ryan had raised six children on her own since 1852 when her husband left Waltham for the gold mines of California and died shortly thereafter. Ida’s father, Albert Morse Ryan, grew up in this fatherless house, where he worked as a painter and milkman. A jack of all trades, he variously described himself as a milkman, a merchant, an Alderman, an auctioneer, a sign painter, and a janitor. Albert Ryan was also an amateur historian and founding board member of the Waltham Historical Society who painted a series of watercolor views of Waltham buildings and streetscapes based on recollections of older members of the community.

Ida Annah Ryan with the Waltham High School Class of 1892. (middle row, third from right). Courtesy of the Waltham Historical Society.

Perhaps Ryan’s father, the aspiring painter, encouraged her to join the Massachusetts Normal Art School where she graduated in 1894. Also in keeping with her father’s involvement in local politics and architectural history, she secured a job as draftsperson in the building department of the City of Waltham in 1895, earning her own wages. She took summer classes in architecture, drawing and mathematics at MIT in 1898 and a few years later enrolled in MIT’s architectural program where she made history as the first woman to earn a master’s degree in architecture (BA 1905; MA 1906) and a travelling scholarship (1907). Throughout her college years, Ida Ryan lived at her family’s house at 19 Hammond Street in Waltham and trained with the local building commissioner, undoubtedly paying her own tuition.

It was not unusual for a turn-of-the-century woman to work in government. By 1900, women occupied one third of federal jobs where they provided clerical support for men. (Collins, 244) Even with her prestigious MIT degrees, Ryan was described as a clerk. For about two decades she worked under Samuel Patch, Jr., a carpenter and wounded Civil War veteran who was 36 years her senior and the only other office worker in the Waltham Building Department. When Patch retired in 1912 at age 75 in poor health, she officially took over as Acting Superintendent of Buildings and Acting Building Commissioner. “She had the active management of the department for 2-3 years; for a much longer time she has been the live wire in that department.” (Boston Globe, 7 Jan 1913)

Inside and outside city government (where she worked from about 1894-1913), Ida Ryan was involved in the construction of numerous houses, renovations to historic structures, and civic and educational buildings in Waltham. Ironically, records of those early commissions are difficult to come by due to the lack of surviving building permits. The practice of recording and filing Waltham building permits for posterity only began in 1912, when Patch retired and Ryan took over the department.

Ida Annah Ryan left clues to her works even when she did not receive credit due to her subordinate role. For example, Samuel Patch is the architect on record for the old Waltham High School (1902, now McDevitt Middle School), but in a tiny signature hidden in the grassy schoolyard Ryan reveals that she was the delineator of the drawings that feature Patch’s name so prominently.

Waltham Public Schools Annual Report, 1901. Courtesy of the Waltham Historical Society.

Most of Ryan’s female peers were in private practice which limited their ability to secure commissions other than private residences, and house design was considered particularly appropriate for women whose traditional sphere was inside the home. (Allaback, 5) In her own firm, Ryan preferred to design “small houses for people of moderate means.” (Boston Globe, April 9, 1911) Historic preservation was another specialty for this daughter of a local historian, just as the country’s first regional historic preservation organization was established in Boston, a few miles away.

In January 1913, Waltham’s newly elected pro-suffrage Mayor shocked politicians, unions, and the system itself when he appointed architect Ida Ryan and lawyer Vera Ryan to high positions in local government. The “Misses Ryan,” who were not related, had served the public for decades in subordinate, low-paying city positions for which they were over qualified. Mayor Duane acknowledged, “A woman must do twice as well as a man and get half the salary.” (Boston Globe, Feb 4, 1918)

Ida Ryan’s fate in this controversial mayoral appointment was played out on the front pages of Boston newspapers. Hers was not merely a local story, but one of a college-educated professional woman who challenged the male status quo in the field of government. That she dared to venture into a field as masculine as the building trades was especially troublesome, for it conflicted with the very definition of womanhood. At the time, women were only beginning to gain acceptance in elected or appointed government positions in schools, libraries and the social sciences which suited their perceived “natural abilities” as nurturers.

Mayor Patrick Duane submitted a petition to legislature to change the local ordinance that stated that “the Inspector of Buildings and his assistants shall be competent men,” but it went nowhere. The Alderman refused to confirm both female appointees, with no discussion and a vote by secret ballot. Some argued that Miss Ryan was holding the office as acting department head illegally.

The Aldermen confirmed Thomas Lally (brother of the lally column inventor) as Superintendent instead, and within a few months he asked for Ryan’s resignation. The mayor intervened on her behalf while she was out of town. She had no knowledge of the compromise Lally and Duane had negotiated before the results were published in the Boston Globe: she could work half time for half the salary.

Ryan resigned in a letter published by the press, creating more upheaval. The Mayor suspended Lally for two weeks, then appointed a new planning board which included two women: namely, Ida Annah Ryan and Mrs. Cecil Walen. When Ryan declined to serve, Mrs. Cecil Warren became the first woman appointed to a planning board in Massachusetts. Thomas Lally returned to his job in the private sector as a bricklayer within a couple of years.

Ida Annah Ryan’s story must have resonated with the rising ranks of college-educated women across Massachusetts who aspired to serve society as men did beyond the home, beyond marriage and beyond parenthood. She confessed, “My work is my life.”

Education: Waltham High School (1892); Massachusetts Institute of Technology ( BA, 1905; MA, 1906)

Waltham Residence: 65 Liberty St., (1873-ca. 1882); 19 Hammond St. (ca. 1882-1918)

Waltham workplaces: Waltham City Hall (ca. 1895-1914); Lawrence Block, Main St. (1912-1918)

Ryan’s Architecture in Waltham

Ida Annah Ryan’s work in Florida in partnership with Isabel Roberts is well studied, but research on her commissions in Waltham is in its very early stages. On the map below, documented works of Ida Annah Ryan or Ryan & Luscomb are pinpointed in red. Single family homes on Ellison Park and Boynton Street anticipate her later work in Florida. City of Waltham projects that took place during Ryan’s tenure in the Building Department are in yellow.

Ryan had a hand in renovating or repurposing several historic structures in Waltham. In her role as a City employee, she must have been involved in an early historic preservation effort prompted by the construction of the new Pond End School in 1912. Rather than simply demolish the old Greek Revival Pond End School (1851) for its modern replacement, the City sold it to a local club to preserve and relocate the historic structure and give it new life as a clubhouse. Her best known work on a historic building was her renovation of the old “Prospect Barn” that stands next to her house on Hammond Street. She purchased the barn and converted it to apartments that offer “plenty of light and sun…[and] maximum of comfort…for people moderate means.” (Boston Globe, 30 April 1911) She must have also been involved in alterations to the adjacent “Prospect House” tavern that was turned on its lot and converted to apartments at the same time. She designed additions to the historic Rev. Thomas Hill house and even a garage addition to Gore Place for its owner, president of the Metz Company automobile manufacturer.

As the only professionally trained architect in the City of Waltham Building Department with a staff of two, she must have been involved in all city building projects in some capacity, either working with the architect on record or possibly playing a more significant role. She occasionally was paid for work within Drawing School and the Engineering Department of the City of Waltham as well.

City buildings constructed or altered during Ryan’s tenure in the Building Department include the old Waltham High School (1902) and about six elementary schools: Plympton (1895, demolished); Chauncy Newhall (1895); Royal Robbins (1901, demolished); Samuel D. Warren (1912); Pond End (1912, demolished) and Thomas Hill (1881, addition 1913). Her involvement in their construction requires further study. In collaboration with the City Engineer, she designed the Woerd Avenue bridge (1905, demolished recently?). In 1904, she showed a project for “A Proposed City Hall” at the Boston Architectural Center annual exhibition.

References:

Albert Morse Ryan Collection, Waltham Public Library

Albert Morse Ryan watercolors, Waltham Historical Society

Allaback, Sarah. The First American Women Architects. University of Illinois Press, 2008

Boston Globe, April 9, 1911; Jan 7, Jan 31, Feb 4, Feb 8, Feb 18, Mar 4, Sept 11, Sept 13, Oct 1, Oct 11, Oct 15, 1913; and Jan 2, 1914.

Collins, Gail. America’s Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates and Heroines, Harper Perennial, 2003.

Inaugural address of Hon. Patrick J. Duane Mayor of the City of Waltham January 6, 1913, with Annual Reports of Several Departments for the Financial Year of 1912. Waltham, Mass., 1913.

Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System (MACRIS), Massachusetts Historical Commission.

Strom, Sharon Hartman. Political Woman: Florence Luscomb and the Legacy of Radical Reform. Temple University Press, 2001.

Waltham Building Department, Building Permits, 1912-1917

Waltham Evening News, March 17, 1913

Waltham High School drawings, Waltham Historical Society.

Stonehurst Curator Ann Clifford wrote this biography in conjunction with “Anxious to Vote: Students, Workers and the Fight for Women’s Suffrage,” a curriculum and public education project developed in partnership by Stonehurst the Robert Treat Paine Estate and Waltham Public Schools in commemoration of the national suffrage centennial in 2020. STONEHURST is a National Historic Landmark owned by the City of Waltham. The once-private estate of social justice advocates whose ancestors helped establish the democratic foundations of this country is now appropriately owned by the people.

The Friends of Stonehurst received support for this program through “The Vote: A Statewide Conversation about Voting Rights,” a special initiative of Mass Humanities that includes organizations around the state.

This program is funded in part by Mass Humanities, which receives support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and is an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.