IDA ESTELLE HALL (1857-1936)

Ida Estelle Hall, lawyer, teacher, suffragist, and “friend of humanity,” organized young immigrant working women for the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA). Her early efforts to recruit wage earners to the women suffrage cause predates well-studied equivalent efforts in New York City by nearly a decade.

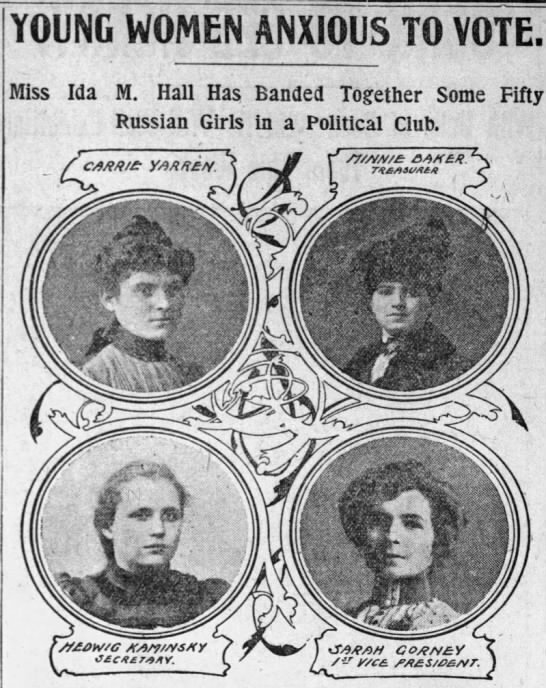

Open to all, her Young Women’s Political Club (YWPC) brought together some “of the most energetic sets of equal rights women in this city…Jewish maidens from imperial Russia.” Since they worked by day, many studied civics and other Americanization classes with Ida Hall in the Boston Evening Schools. In its first year, 1899, one YWPC member “got naturalized…so that she might vote for the school committee. Another organized a tobacco strippers’ union.” Several attended Boston University. (Boston Globe, May 5, 1902, p. 3)

Like many of her students, Ida “Stella” Hall had humble beginnings and earned her own living. She came from a family of self-sufficient women who worked as seamstresses in a North Reading intergenerational household devoid of men. Her home life was in constant flux, with her parents often living under separate roofs even before her father left North Reading to serve in the Civil War and then to live in a home for disabled veterans. Ida Hall chose an independent path for a woman of her time, graduating from Salem State Normal School in 1876, and teaching in North Reading, Woburn and Somerville for two decades. She never married. At the age of 38, Hall resigned from her teaching position in Somerville to attend law school at Boston University, run for School Committee, and devote her energies to women’s suffrage.

Her motivation for such a dramatic career change was undoubtedly the great pay inequity between male and female teachers in the Massachusetts schools. She earned a salary a mere third of that of her male colleagues. (Boston Journal, Nov 7, 1895) As a self-supporting teacher turned lawyer she was in a unique position to bridge the divide between trade union workers who wanted power over the labor laws that affected their lives and the college-educated women who developed and administered labor legislation. (Dubois, 50)

Hall first appears as one of the “brainy orators” at a New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) meeting for young suffragists in 1895. “At this meeting, the conventional idea of the traditional woman suffragists with the face of a termagant who wields threateningly an ungainly green umbrella was completely upset.” NEWSA leader Alice Stone Blackwell introduced Stella Hall as one of the “new women” of the women’s suffrage movement: young, attractive, feminine and smart. (Boston Journal, May 29, 1895)

As she was studying for her law degree, she funded her sisters’ college educations by teaching at the Boston Evening Schools, and ran a house-to-house canvas for women’s municipal suffrage in every ward of Somerville, “the best organized city in the state.” Her canvas work for municipal suffrage in 1895 with the Ward and City Committee of Female Voters of Somerville was described by Boston reporters as “probably unprecedented in any city in New England.” (Boston Post, Oct 9, 1895; Boston Globe, Sept 18, 1895, Boston Daily Advertiser, June 3, 1897)

After passing the Massachusetts bar in 1897, Ida Hall began her work for equal rights in earnest by organizing and legislating at the state level for the MWSA. As the “superintendent among working women,” she soon formed the Young Women’s Political Club as an official arm of the association. (Boston Herald, Jan 26, 1899) The make-up of YWPC membership would complement that of its better known counterpart, the College Equal Suffrage League formed in 1900. In the next few years, the two organizations for young women representing the spectrum of economic classes held joint rallies “with sociological meaning” for their common cause.

At the Faneuil Hall rally Ida Hall organized in 1901, she invited a diverse bodies of speakers including Irish-American union organizer Mary Kenney O’Sullivan, Jewish lawyer and business woman Diana Hirschler, and Seniorita Huidobro of Chile. As a lawyer and civics teacher, Hall spoke of the history she knew so well: the “mass meeting here 140 years ago founded a great nation, but left injustices and inequities that burn and rankle and which remain to be adjusted.”

That evening, Boston-based national labor organizer Mary Kenney O’Sullivan first publicly announced her support—and therefore critical Union support—for the women’s suffrage cause. A reporter paraphrased O’Sullivan: “With the advent of such organizations as the hosts of the evening, there appeared to be a chance for new ideas.” (Boston Herald, April 14 & 17, 1901; Boston Globe, April 17, 1901)

O’Sullivan would famously go on to co-found the national Women’s Trade Union League in Boston in 1903 and speak from the labor perspective for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NASWA) at the US Capitol in 1906. (Nutter) The women’s suffrage and labor movements gained momentum in 1907 when the American Federation of Labor (mostly men) committed to “equal suffrage, equal rights and equal pay” and when Harriet Stanton Blatch founded the influential Equality League for Self-Supporting Women in New York City. Workers like Rose Schneiderman “brought to the movement both a new perspective on suffrage and a provocative, street-smart campaign style.” (Berenson, 104-105; Orleck, 89; Dubois) By late 1907, the NASWA observed “it will not be the educated workers, the college women, the men’s association for equal suffrage, but the people who are fighting for industrial freedom who will be our vital force at the finish.” (Progress, Nov 1907) This was no longer a movement of any single class but one that united people of all economic levels.

As Ida Hall moved to Waltham in 1907, then, she must have felt energized by national headlines dominated by the more inclusive, cross-class thread of the woman’s suffrage movement, a cause in which she had played a pioneering role.

In Waltham, a city of thousands of female watch and textile factory workers, Ida Hall founded and headed the Waltham Suffrage League and maintained ties to Boston through MWSA and the Boston schools. (Boston Globe, Oct 26, 1912, Boston Herald, Oct 16, 1907) In 1912, she and her sister Josephine (a local Latin teacher and suffragist) purchased one of the first houselots on Chesterbrook Road from wealthy and influential supporters of workers’ rights: Ethel Paine Moors and other heirs of Robert Treat Paine. From her new bungalow on the edge of the Paines’ woods, Hall helped publish a suffrage edition of the local paper, hosted rallies on the common, represented female teachers in their battle for equal pay for equal work, and even held a suffrage forest party by her house. (Boston Journal, Mar 19,1913; Boston Herald, June 1 and June 29 1913; Waltham Evening News Mar 17 and June 16, 1913; Boston Globe Jan 17, 1917 and Dec 2, 1920) Always committed to working women’s rights, she taught students in the Waltham Evening Schools, inspiring them to embrace their rights and responsibilities in our democratic society.

Education: Salem State Normal School, 1875; Boston University, LLB, 1897

Waltham residences: 37 Pond St (1907-1909); 48 Vernon St (1910-1912); 50 Chesterbrook Rd. (1912-1936)

References

Berenson, Barbara. Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement. The History Press, 2018.

Dubois, Ellen Carol. “Working Women, Class Relations, and Suffrage Militance: Harriot Stanton Blatch and the New York Woman Suffrage Movement, 1894-1909.” The Journal of American History, June 1987, vol 74, no. 1 (June 1987), pp. 34-58.

Nutter, Kathleen Banks. The Necessity of Organization: Mary Kenney O’Sullivan and Trade Unionism for Women, 1892-1912. Routledge, 2019.

Orleck, Annelise. Common Sense and a Little Fire: Working Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965. University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Stonehurst Curator Ann Clifford wrote this biography in conjunction with “Anxious to Vote: Students, Workers and the fight for Women’s Suffrage,” a curriculum and public education project developed in partnership by Stonehurst the Robert Treat Paine Estate and Waltham Public Schools in commemoration of the national suffrage centennial in 2020. STONEHURST is a National Historic Landmark owned by the City of Waltham. The once-private estate of generous social justice advocates whose ancestors helped establish the democratic foundations of this country is now appropriately owned by the people.

The Friends of Stonehurst received support for this program through “The Vote: A Statewide Conversation about Voting Rights,” a special initiative of Mass Humanities that includes organizations around the state.

This program is funded in part by Mass Humanities, which receives support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and is an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.