Young women like Florence Luscomb inspired students and workers across Massachusetts to fight for equal rights.

“As those of us who have been working for suffrage for years grow older and more tired, it is a great comfort to know that there are brave young women coming on to fill up the ranks.” Alice Stone Blackwell to Florence Luscomb, Jan 27, 1910.

Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

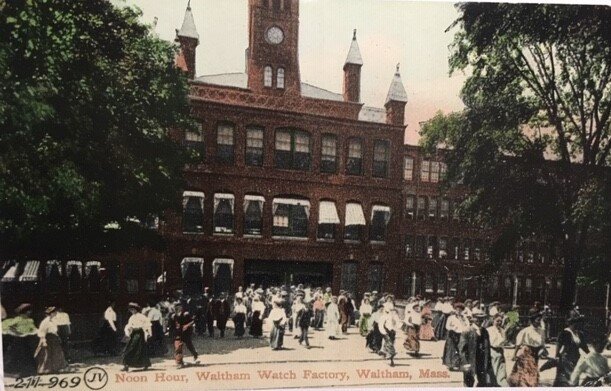

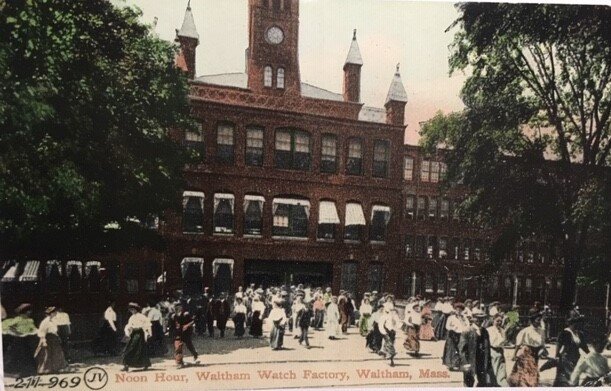

Some young people work in factories during the day and go to school at night. In the streets and in civics class with teachers like Ida Hall, they learn about democratic government.

“As the workers came out at noon we gave out the bills and announced speaking at half past…. The audience was there ready to be entertained, often sympathetic in advance.” — Florence Luscomb.

”Their knowledge of public affairs is astonishing.” —Ida Hall.

Postcard: Waltham Historical Society

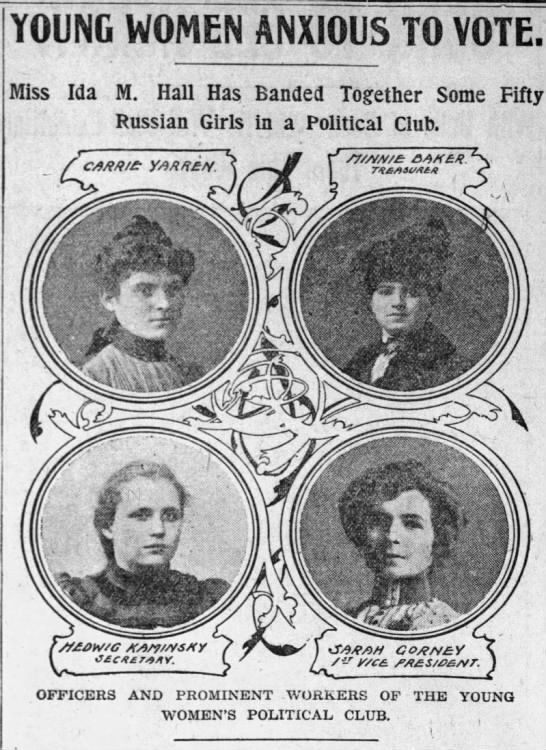

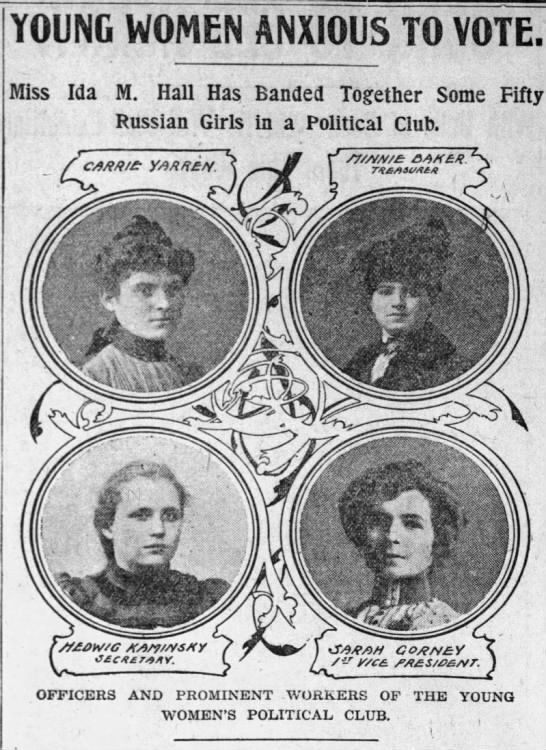

Night school students formed political clubs with the help of teachers like Ida Hall.

“Under the old thought a girl must marry, keep house, bear children and live a life of servitude to them and to her husband. Now, she is often broad-minded and well educated and possesses all of the qualifications required of men who vote. Why, then, should she not vote?” Sarah Gorney, Russian immigrant, age 25. The Boston Globe, May 5, 1902, p. 3.

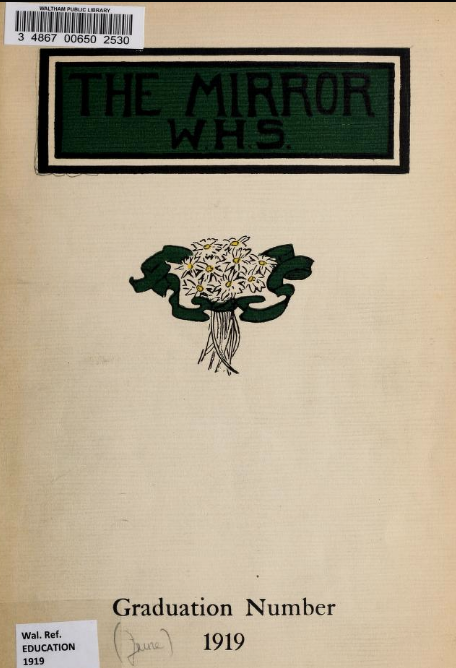

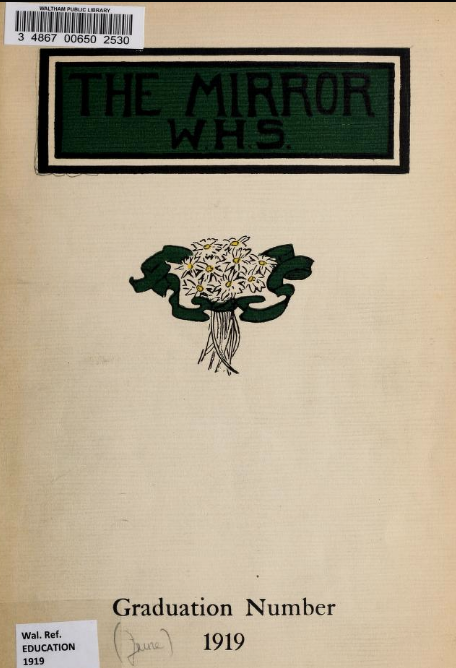

Some Waltham High School students showed their support for women's suffrage with yellow roses.

“One day [Latin teacher Ms. Josephine Hall] brought yellow roses which she distributed…to those who claimed an uncorruptible faith in woman suffrage.”

Hannah Webster, age 17, “History of the Class of 1919,” Waltham Mirror, 1919, p. 152. Waltham Public Library

Activists young and old work together on the fight for equality.

Here, Florence Luscomb, teachers Ida and Josephine Hall, and other suffragists took over the local paper. When Luscomb was a student in college, “any notices of the suffrage meetings put up on the bulletin boards were immediately torn down.”

"Suffragette" was a word used to mock suffragists, especially the more militant suffragists in England.

Florence Luscomb’s valentine to her mother, 1910. Luscomb Collection, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

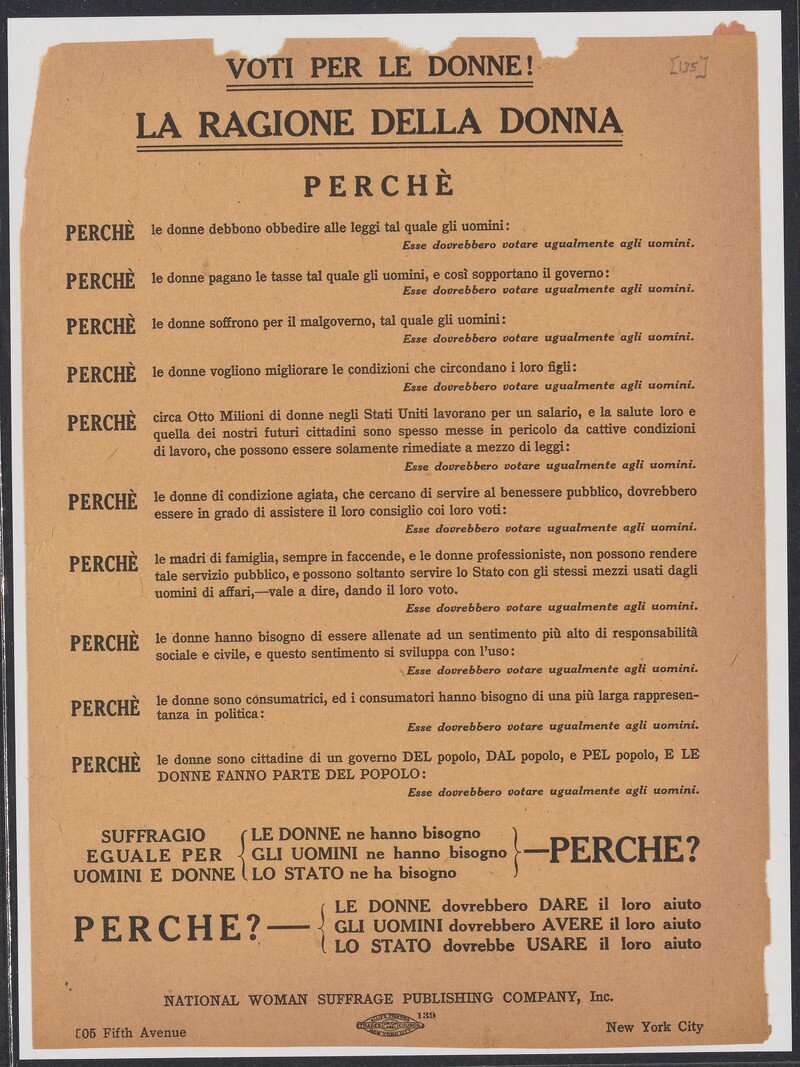

Many students learn new languages to get by at work, school and home. To reach all families, suffragists know they need to speak multiple languages.

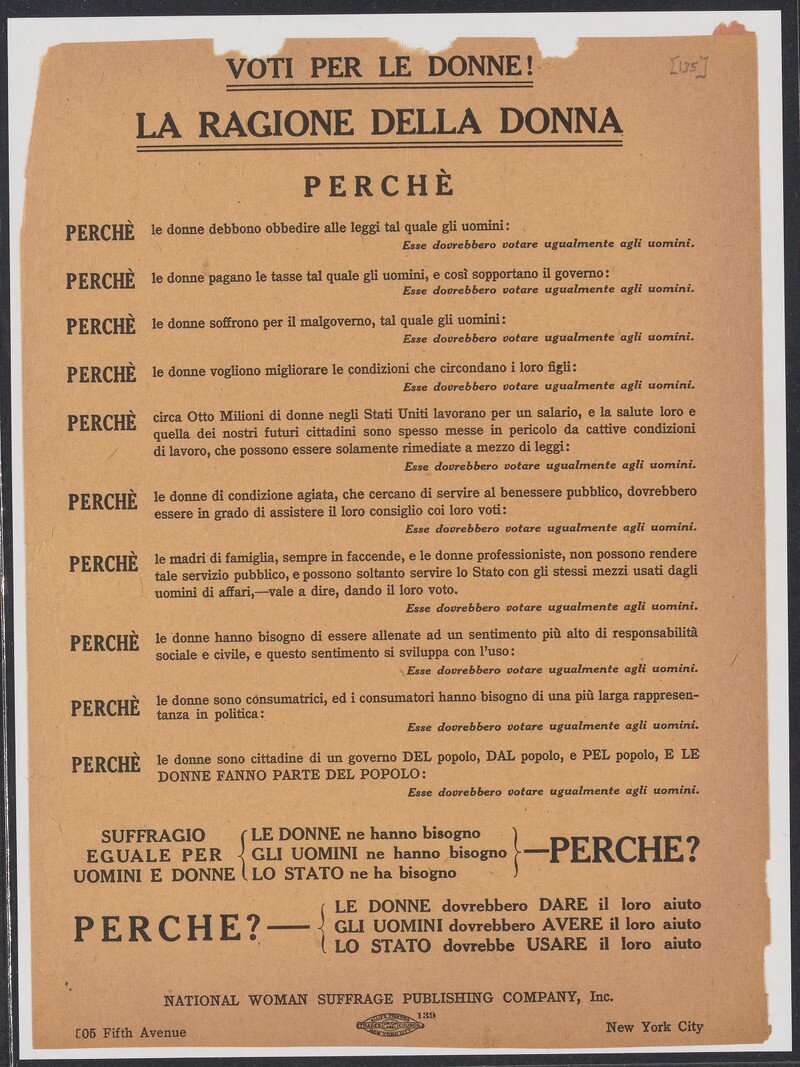

“PERCHE le donne sono cittadine di un governo DEL popolo, DAL popolo, e PEL popolo, E LE DONNE FANNO PARTE DEL POPOLO.” Women’s suffrage leaflet in Italian. Florence Luscomb Papers. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Lessons in civics take on a special meaning when working long hours in dangerous conditions for little pay.

“A man and woman are working at the same piece of work, obtain the same results and spend an equal time on it, but when paying time comes, the woman’s salary is just half or one third of the man’s. Why? Because she is a woman and can’t help herself and he is a man and can vote.” — A Girl of 12 quoted in the Waltham Evening News, March 17, 1913.

Photo: Spinning Room, Cornell Mill, Fall River, Mass. by Lewis Hine, 1912. National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress.

Some students have to work to support their families.

“[In the] Evening Schools…. The chief subject of instruction is the English language, but some attention is given to civics, particularly for children of foreign birth.” —Margaret Hutton Abels, From School to Work, 1917.

When teachers took over the local newspaper for a day, one student published this article, "Why I Believe in Equal Suffrage".

“A man and woman are working at the same piece of work, obtain the same results and spend an equal time on it, but when paying time comes, the woman’s salary is just half or one third of the man’s. Why? Because she is a woman and can’t help herself and he is a man and can vote.” — A Girl of 12, Waltham Evening News, March 17, 1913.