Ida Hall was the first to organize young working women for the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association as early as 1899. Many of her recruits were her students in the Boston Evening Schools who had recently immigrated from Europe and worked in low-paying, low-skill jobs during the day. Hall’s Young Woman’s Political Club in Boston predates the famous wage earners leagues of New York City by nearly a decade.

By late 1907, the NASWA observed “it will not be the educated workers, the college women, the men’s association for equal suffrage, but the people who are fighting for industrial freedom who will be our vital force at the finish.” (Progress, Nov 1907) This was no longer a movement of any single class but one that united people of all economic levels.

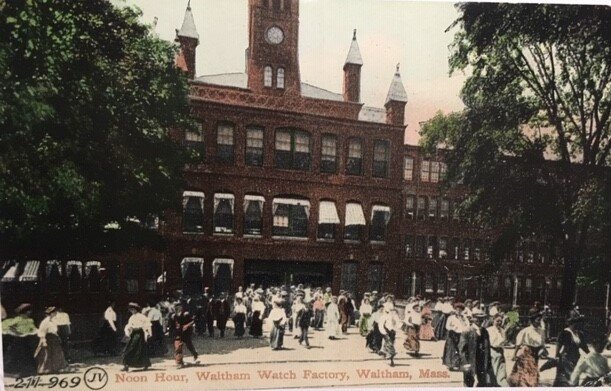

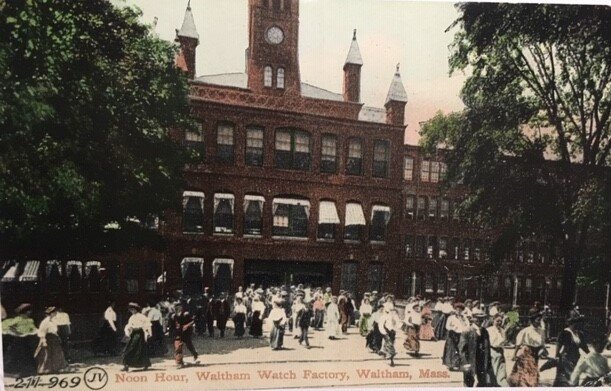

Noon Hour, Waltham Watch Factory.

In 1903, as many as 3,000 women worked in the Waltham Watch Factory. Massachusetts women suffragists like Waltham’s Florence Luscomb and Amy Acton recruited factory workers during their “noon hour” break through open air speeches, leaflet distribution and interviews.

Dozens of photos of women working in the Waltham Watch Factory are available in Harvard’s Curiosity Collection on Working Women.

Postcard: Waltham Historical Society

Waltham High School Year Book, 1919

This issue describes how teacher Josephine Hall consoled students with flowers when a Waltham high school student died in World War I. Students committed to women’s suffrage received yellow roses.

The full year book is available through the Waltham Public Library

Josephine Hall lived with her sister Ida Hall on Chesterbrook Rd.

Boston Herald, Mar 18, 1913

This article about women taking over the local press for a day, three of the most active suffragists are shown together in a single image: Ida Hall, her sister Josephine Hall and Florence Luscomb.

Spinning Room, Cornell Mill, Fall River, Massachusetts, 1912

Massachusetts textile mill workers might have chosen bobbins of cotton thread to represent themselves and their workplace. This representative photo shows women and children surrounded by thousands of such bobbins.

In Waltham and Lowell, the cotton mills owned by the Boston Manufacturing Company were operated by young mill girls from the start. The BMC mill in Waltham was the first integrated factory in America, established in 1814, nearly a century before this photo was taken.

During the Progressive era, photographers such as Lewis Hine gave Progressive reformers the tools to share the evidence of the harsh reality of child labor. Congress proposed a child labor amendment in 1924, but Massachusetts and other states failed to ratify it, empowering the opposition. Not until 1938, as part of the Fair Labor Standards Act, would child labor be illegal on the federal level. For more information, see: Child Labor in the United States Lewis Hine photo, 1912. National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress.

Foreign language leaflet

Suffragists distributed flyers in many languages to reach foreign-born men and women.

Florence Luscomb Papers. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

From School to Work,

Progressive reformers did their best to highlight working conditions, especially for women and children, through exhaustive investigations, documented in reports such as this.

For more information, see: United States Children's Bureau

For the full report on Waltham, and a description of the Waltham Evening Schools where Ida Hall taught, see From School to Work

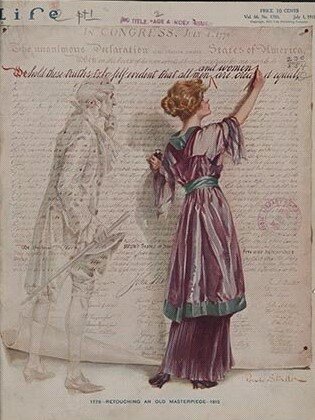

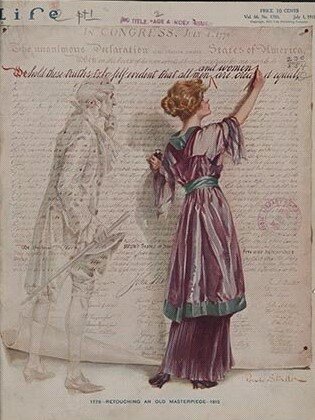

"Retouching an Old Masterpiece," Life Magazine, 1915

According to American political scientist Larry Diamond, democracy consists of four key elements: a political system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; the active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; protection of the human rights of all citizens; a rule of law, in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens.[9]” https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Democracy

This Life Magazine cover relates to the biography of Ethel Paine, a great great granddaughter of a signer of the Declaration of Independence. A copy of this document hangs in the Great Hall of her country house in Waltham called Stonehurst.

Library of Congress

President Wilson's War Message, 1917

Women suffragists were the first Americans to dare to picket the White House. Here, these picketers for the National Woman’s Party, known as silent sentinels, used President Woodrow Wilson’s own words against him.

For more information, see Tactics and Techniques of the National Woman’s Party Suffrage Campaign.

Most historians of women’s suffrage emphasize the impact of WWI on the movement’s increasing success once the United States entered the war in 1917. See: Suffrage and WWI

"Ancient History," Life Magazine, Feb 20, 1913

The modern American democratic experiment was inspired by the political systems of ancient Greece and Rome. Even in these ancient democracies and republics, women could not participate in political life.

This long history of exclusion gave ample fuel to opponents who often treated modern women suffragists with ridicule, as seen in this tongue-in-cheek magazine cover. The central figure with the umbrella represents Susan B. Anthony.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_democracy#Historic_origins

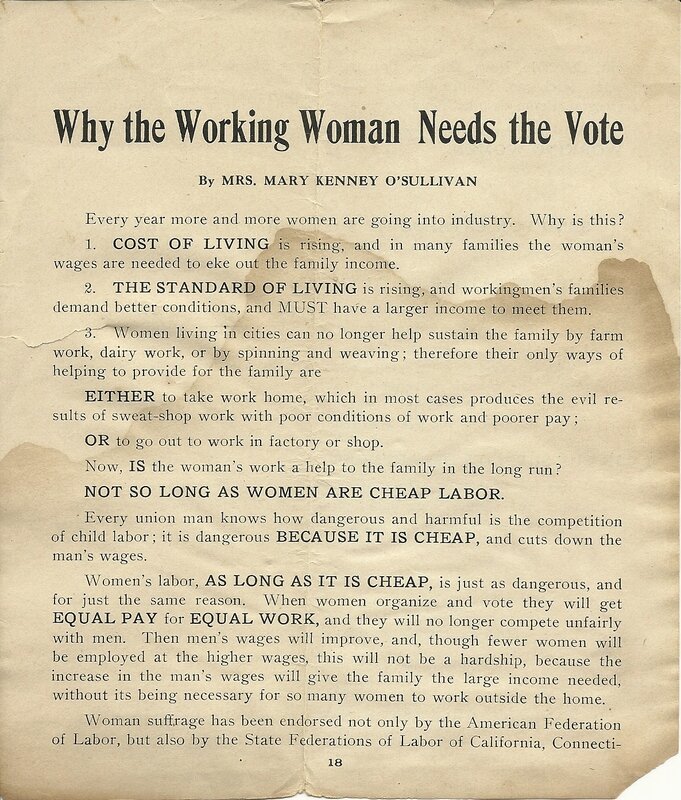

Ida Hall organized this important meeting in Faneuil Hall which brought together young working women and college-educated women. Its diverse body of speakers included labor leader and future WTUL founder Mary Kenney O’Sullivan who pledged her alliance to women’s suffrage for the first time. See Ida Hall’s biography

"They Alone Cannot Vote," Woman's Journal, 1915

It can not, nor should it be, denied that some in the movement relied on racist, classist, and elitist arguments for women’s suffrage: Overt Racism after 1890

"Women to the Rescue!" The Crisis, May 1916.

This illustration in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) journal The Crisis was created by and for African-Americans. Those who campaigned for women’s suffrage also pursued a campaign against racism.

Anti-suffragists in Boston repurposed this image to support their case against women’s suffrage. Sadly, many women suffragists who were not Black excluded African-American women in order to win support in the South.

Formerly enslaved Emma Jennings lived with a Waltham family who supported women’s suffrage, but her own ideas on the subject are unknown. Famous African-American women who were active in the women’s suffrage movement include Mary Church Terrell in D.C., Ida B. Wells-Barnett in Chicago and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin in Boston.

For more on this anti-suffrage button, see https://votesforwomen.cliohistory.org

Political buttons have an interesting history of their own: Campaign button

So, it’s not surprising that the women’s suffrage movement would produce a multitude of buttons: http://womansuffragememorabilia.com/woman-suffrage-memorabilia/suffrage-buttons/

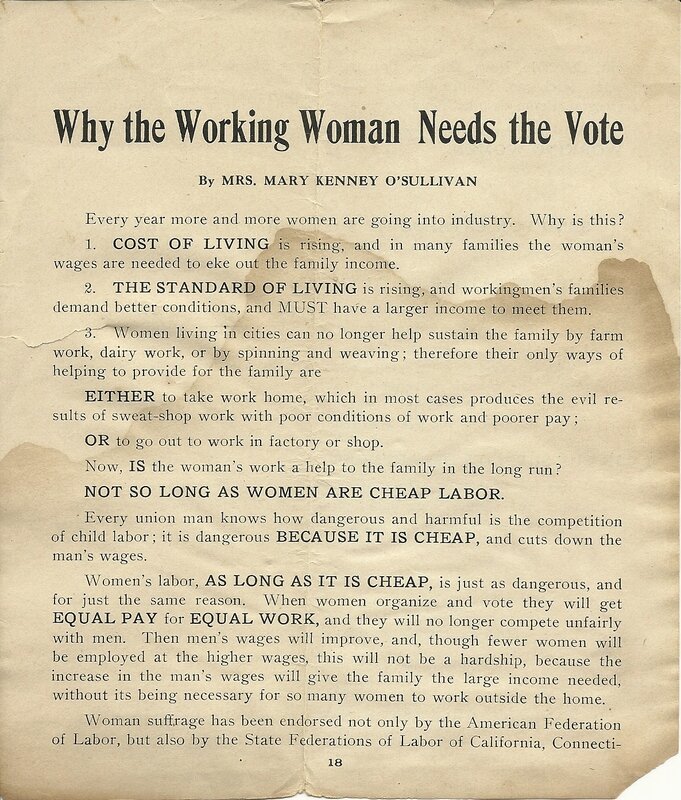

For more information on Boston-based labor leader and co-founder of the national Women’s Trade Union League, Mary Kenney O’Sullivan, see: O'Sullivan, Mary Kenney (1864–1943)

O’Sullivan lived in a the Denison settlement house in Boston, which was lead by two Waltham residents: Helena Dudley, Cornelia Warren. Waltham’s Ethel Paine was also involved in Denison House.

Source: Ann Lewis Women’s Suffrage Collection. From the collection of Ann Lewis and Mike Sponder.

Yellow roses—and the colors yellow and gold—were popular symbols of the women’s suffrage movement. The red rose—and the color red—symbolized one’s affinity with anti-suffragists. A debate over the ratification of the 19th Amendment in Tennessee was called The War of the Roses. Symbols of the Women's Suffrage Movement (US National Park Service)

Today, Massachusetts middle school students advocate for the passage of the Equal Rights Act using the moniker The Yellow Roses.

Waltham teacher Josephine Hall handed out yellow roses to her high school students. (See Waltham yearbook, 1919). A large anti-suffrage parade in Boston organized by Waltham’s Evelyn Sears was described by the press as “A Riot of Red Roses.” (Fall River Evening News, Oct 15, 1915.)

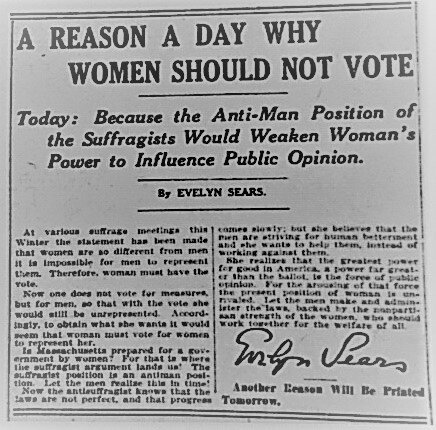

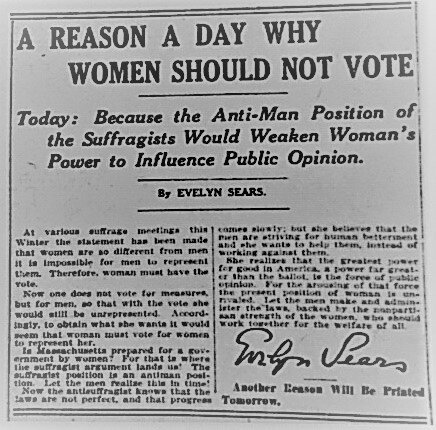

Waltham resident and professional tennis player Evelyn Sears briefly led the Massachusetts Anti-Suffrage Association. Like many anti-suffragists, she belonged to one of the wealthiest families in the Massachusetts. However, her equally wealthy cousin Ethel Paine and her sisters quietly supported women’s suffrage. See Evelyn Sears

Boston Globe, April 4, 1913.

Common Mistakes About Suffrage

Racist, classist, elitist, and nativist arguments were not uncommon in the women’s suffrage movement. For example, see: How Midwestern Suffragists Won the Vote by Attacking Immigrants

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College.

Suffragists gained the support of influential men like Robert Treat Paine of Waltham through common causes such as international peace. Many prominent women such as Alice Stone Blackwell and Helen Keller of Massachusetts were deeply involved in both the women’s suffrage and world peace movements. See the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. .

In addition to running the American Woman Suffrage Association and the Woman’s Journal, Alice Stone Blackwell was the only female board member of the American Peace Society. Her father Henry Blackwell wrote this article for the Woman’s Journal. Ethel Paine, daughter of the Peace Society’s president, was pro-suffrage and an ardent pacifist.

On the other hand, even many suffragists committed to pacifism chose to support the nation’s entry into WWI because they believed that support for the war would help achieve their own goal for a constitutional amendment.

Woman’s Journal May 16, 1896.

Florence Luscomb practicing for a suffrage campaign, Allston, Mass., 1909

For more information on Luscomb, see Florence Luscomb

For her activism in Waltham, see stonehurstwaltham.org/florence-luscomb

Photo: Florence Luscomb collection, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

Massive parades were a vital tactic in the women’s suffrage movement, beginning with the famous 1913 parade organized by Alice Paul and Lucy Stone on the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s election. This first large-scale political protest in Washington, DC, drew national attention and sympathy to the cause. The unfortunate mistreatment of women and inadequate police protection ultimately worked in their favor.

https://guides.loc.gov/american-women-essays/marching-for-the-vote

Waltham architect Florence Luscomb and her mother participated in this parade.

Scholar Barbara Berenson describes The Women’s Journal, founded by Lucy Stone and published in Boston from 1870-1917, as “the communications hub for the women suffrage movement.” It is searchable on line. Woman’s Journal

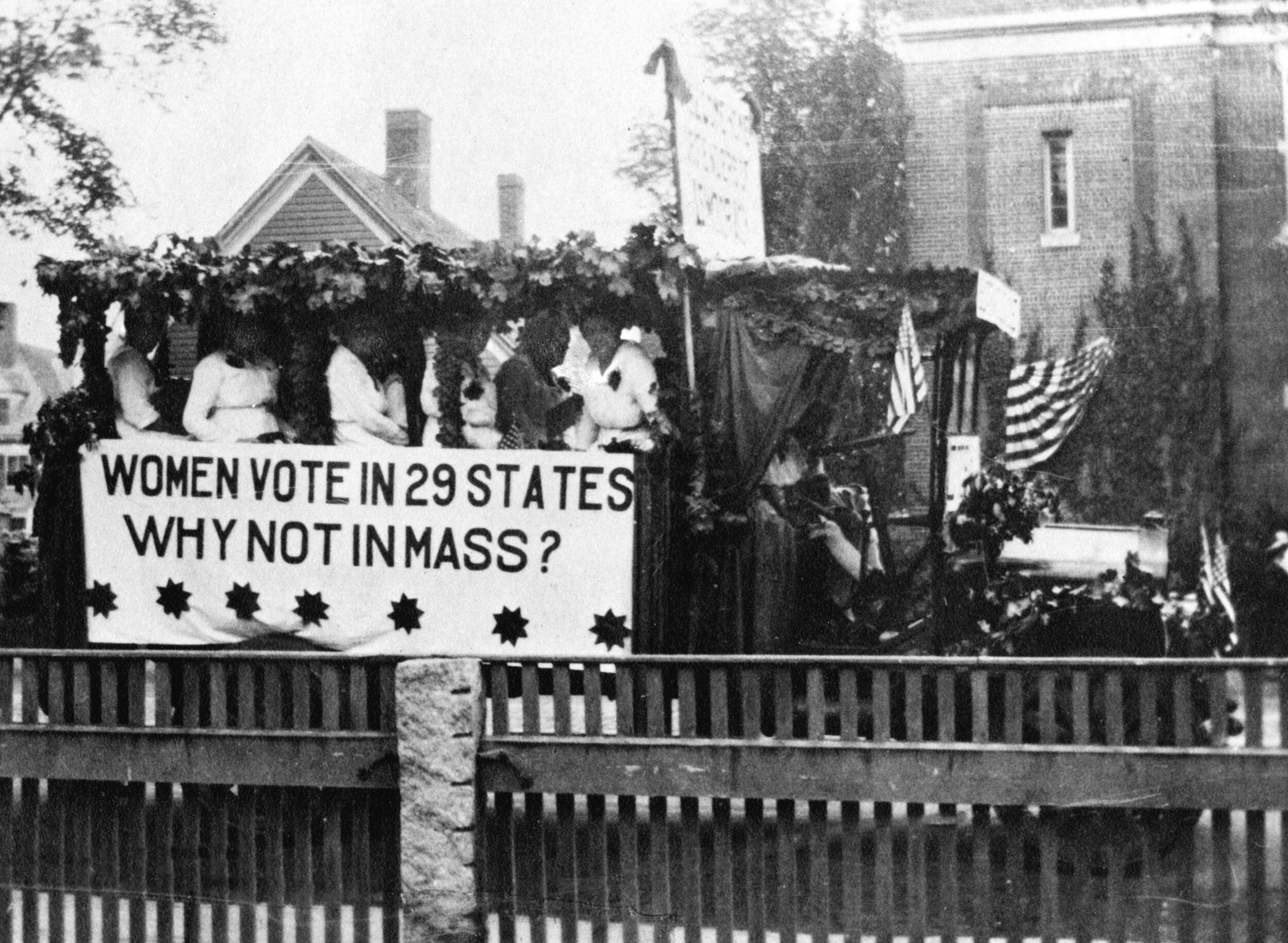

Waltham architects Ida Annah Ryan and Florence Luscomb created many local suffrage floats powered by both by horses and by automobile. This “Victory” float from June 17, 1919 celebrated the return of World War I soldiers just days before the ratification of the 19th Amendment by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts on June 26, 1919.

In 1919, it was still rare for women to drive vehicles.

Photo: Main St., Waltham, Mass. June 17, 1919. Waltham Historical Society. The Waltham Public Library also has two photos of this float.

Suffrage bluebird, by Waltham architect Florence Luscomb, 1915

100,000 of these iconic bluebirds designed by Waltham architect Florence Hope Luscomb were posted on barns, fences and shop windows across Massachusetts as part of a 1915 referendum campaign. These cheery bluebirds, symbols of hope, have come to represent the creativity and resilience of women suffragists across the nation.

Despite an energetic 1915 campaign, the majority of the male electorate in Massachusetts voted against the referendum for a state constitutional amendment to enfranchise women. Defeats in the Northeastern states that November caused suffragists to pivot and focus instead on an amendment to the federal constitution.

National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Margaret Foley in a hot air balloon at a suffrage rally, Lawrence, Mass., Aug 1910.

From the air, Foley dropped thousands of foreign language leaflets over factory workers in Lawrence, Mass.

For more on Luscomb’s friend, Margaret Foley, see Margaret Foley (suffragist)

Margaret Foley Collection, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

These Bills For the Welfare of Women and Children were Defeated"

Year after year, Waltham lawyer Amy Acton presented bills to Massachusetts legislature on behalf of the Mass Women’s Suffrage Association and working women and children.

This series of defeats only underscored the need for women’s active participation in politics and strengthened their resolve.

Suffragists and workers joined forces in earnest after the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire in 1911 brought national attention to the gruesome working conditions of young working-class women, immigrant and native born alike.

https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/a-vital-force-immigrant-garment-workers-and-suffrage

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

Waltham’s pro-suffrage mayor (and former bobbin boy) Patrick Duane shook up the status quo when he appointed two women for senior city positions. Ida Ryan and Vera Ryan briefly served as acting department heads for a fraction of the salary of their male counterparts. The mayor was unsuccessful in seeking an act of legislature that would allow women to become department heads, so neither appointment was confirmed. See Ida Annah Ryan

Source: The Boston Globe, Jan 7, 1913.

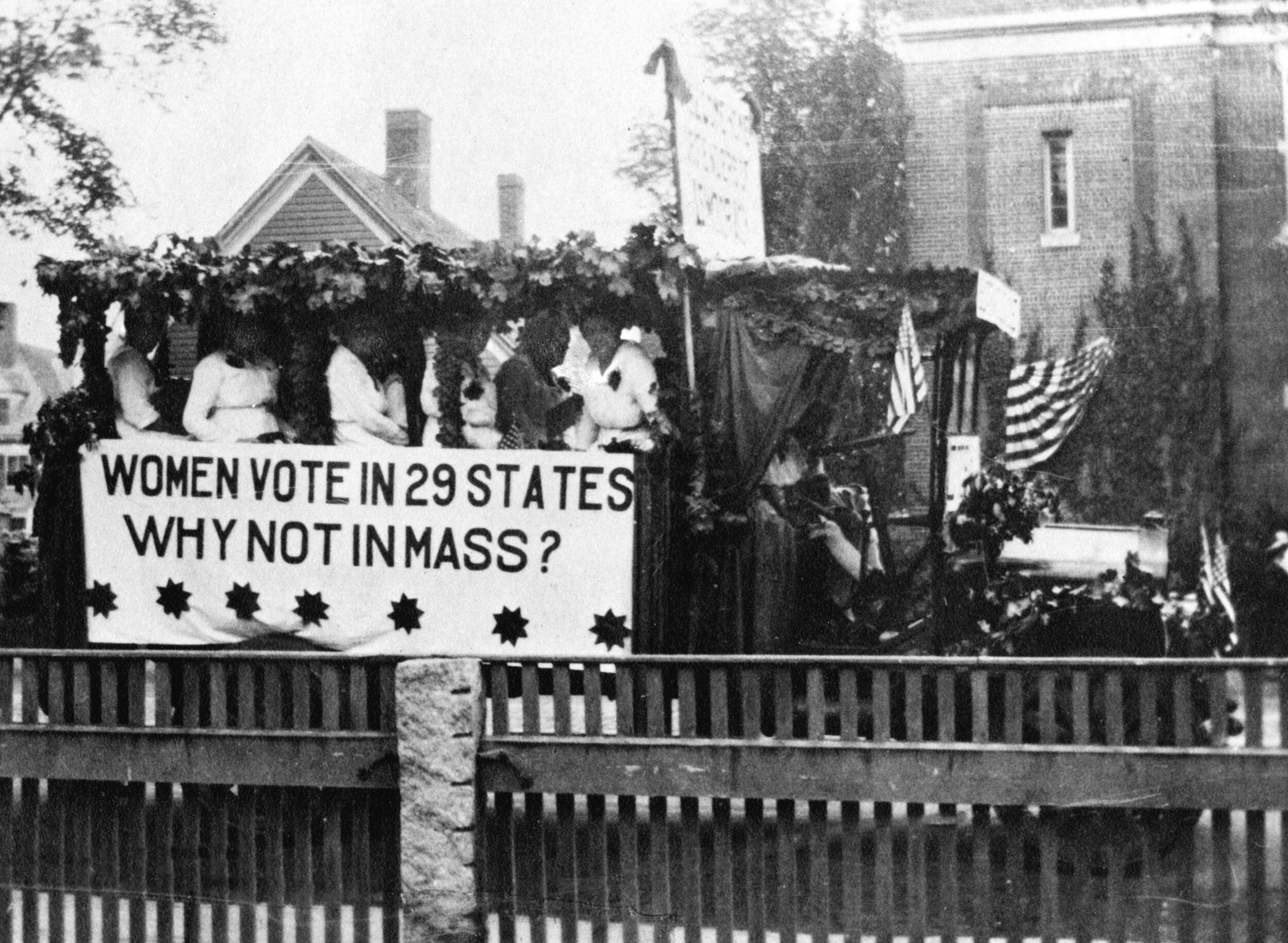

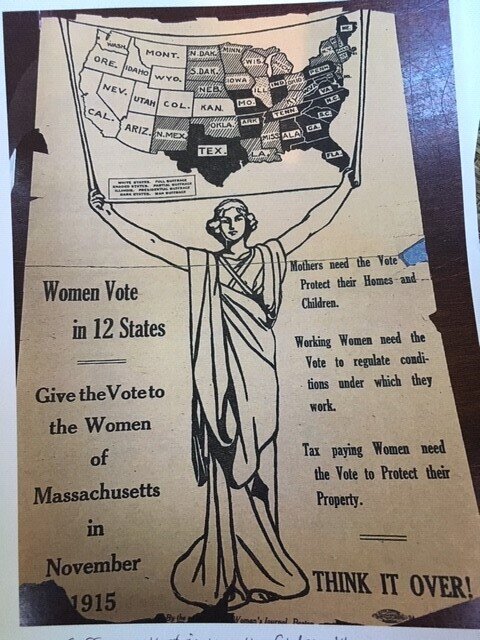

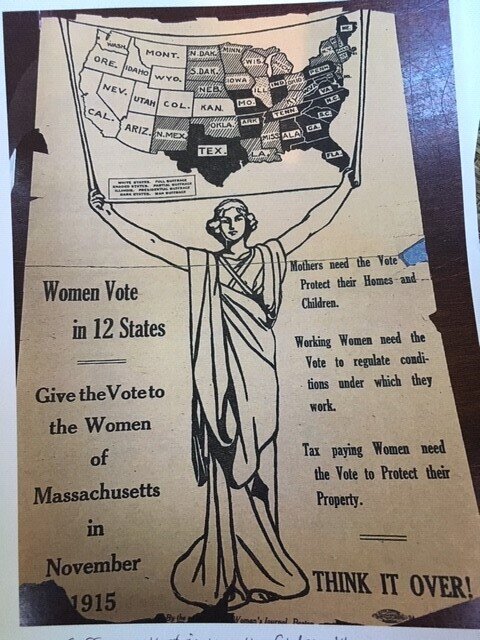

"Women Vote in 12 States," 1915

For many decades, suffragists slowly built local and state support for women’s voting rights and achieved victories in western territories and states. They mapped the progress of the women’s suffrage movement in each state with persuasive political maps.

State referenda were defeated in 1915 in the Northeast and were inconceivable in the South, but this state-based strategy was an essential prerequisite to achieve support for a federal amendment which would require ratification by three quarters of the states.

https://constitutioncenter.org/timeline/html/cw08_12159.html

Source: Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

Ratification of the 19th Amendment by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, June 25, 1919

A constitutional amendment requires the support of two thirds of the House and Senate followed by ratification by three quarters of the states.

Even once the US Congress passed the 19th Amendment, 36 of the then 48 states needed to ratify it so the state-level work continued:

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/womenshistory/19th-amendment-by-state.htm

Florence Luscomb painting in Tennessee on the Ratification Map, June 5, 1919.

A 24-year-old Senator from Tennessee dramatically broke the tied vote after being urged by his mother to “be a good boy” and vote for ratification. Read the story as told in the NY Times

Source: Florence Luscomb Collection, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

Manual for Massachusetts Voters, 1920

And the work continues: League of Women Voters

Florence Luscomb co-authored this manual that was distributed to students in the Boston Public Schools.

Women's Suffrage Banner, 1913-1920

Like buttons, pennants and other memorabilia were important symbols for the women’s suffrage movement. For more information, see: https://www.nps.gov/articles/symbols-of-the-women-s-suffrage-movement.htm