1920

VOTING RIGHTS TIME CAPSULE

ANXIOUS TO VOTE: STUDENTS, WORKERS AND THE FIGHT FOR WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE

A curriculum and public education project, 2020

Explore the contents of this fictional 1920 voting rights time capsule which is meant to represent the work of students of Ida and Josephine Hall, long-time educators and activists in the industrial city of Waltham, Massachusetts. The documents and characters are true to history, but the captions are fictional.

Before “opening” the time capsule,

Watch this introductory video:

https://www.pbs.org/video/womens-suffrage-7neirw/Read this introductory text:

https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=6

Look closely at the time capsule box. “Inside,” you will find five bundles of objects and documents.

Contents of the Time Capsule

Women across the country finally won access to the ballot box in 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

“The rights of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be abridged or denied by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

”

A great army of women in towns and cities across the nation campaigned for nearly a century to win the right to vote. The task was challenging. Suffragists had to persuade men, who possessed all the political power, to share it.

“Unwrap” each bundle for students’ and workers’ perspectives on the struggle for women’s suffrage, or the right to vote in political elections.

ABOUT US

Young people bring energy, creativity and exposure to the long struggle for equal voting rights.

“As those of us who have been working for suffrage for years grow older and more tired, it is a great comfort to know that there are brave young women coming on to fill up the ranks.” Alice Stone Blackwell to Florence Luscomb, Jan 27, 1910.

Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

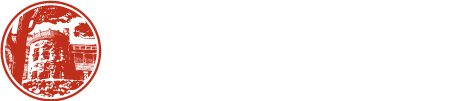

“As the workers came out at noon we gave out the bills and announced speaking at half past…. The audience was there ready to be entertained, often sympathetic in advance.” — Florence Luscomb.

”Their knowledge of public affairs is astonishing.” —Ida Hall.

Postcard: Waltham Historical Society

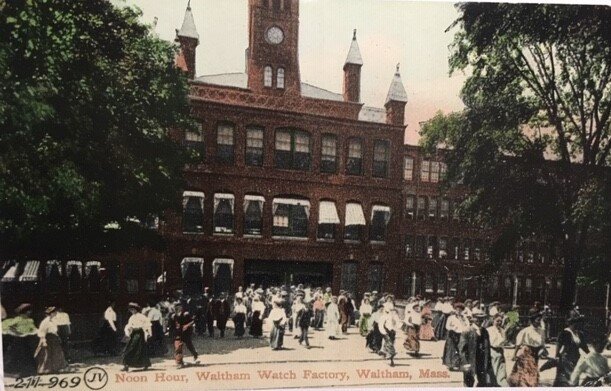

“Under the old thought a girl must marry, keep house, bear children and live a life of servitude to them and to her husband. Now, she is often broad-minded and well educated and possesses all of the qualifications required of men who vote. Why, then, should she not vote?” Sarah Gorney, Russian immigrant, age 25. The Boston Globe, May 5, 1902, p. 3.

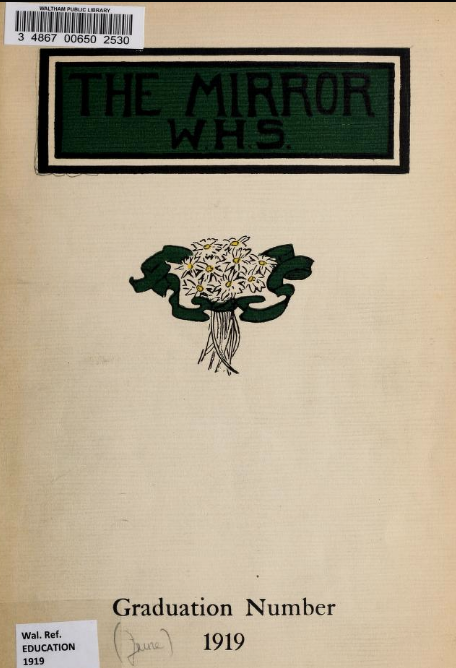

“One day [Latin teacher Ms. Josephine Hall] brought yellow roses which she distributed…to those who claimed an uncorruptible faith in woman suffrage.”

Hannah Webster, age 17, “History of the Class of 1919,” Waltham Mirror, 1919, p. 152. Waltham Public Library

Here, Florence Luscomb, teachers Ida and Josephine Hall, and other suffragists took over the local paper. When Luscomb was a student in college, “any notices of the suffrage meetings put up on the bulletin boards were immediately torn down.”

Florence Luscomb’s valentine to her mother, 1910. Luscomb Collection, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

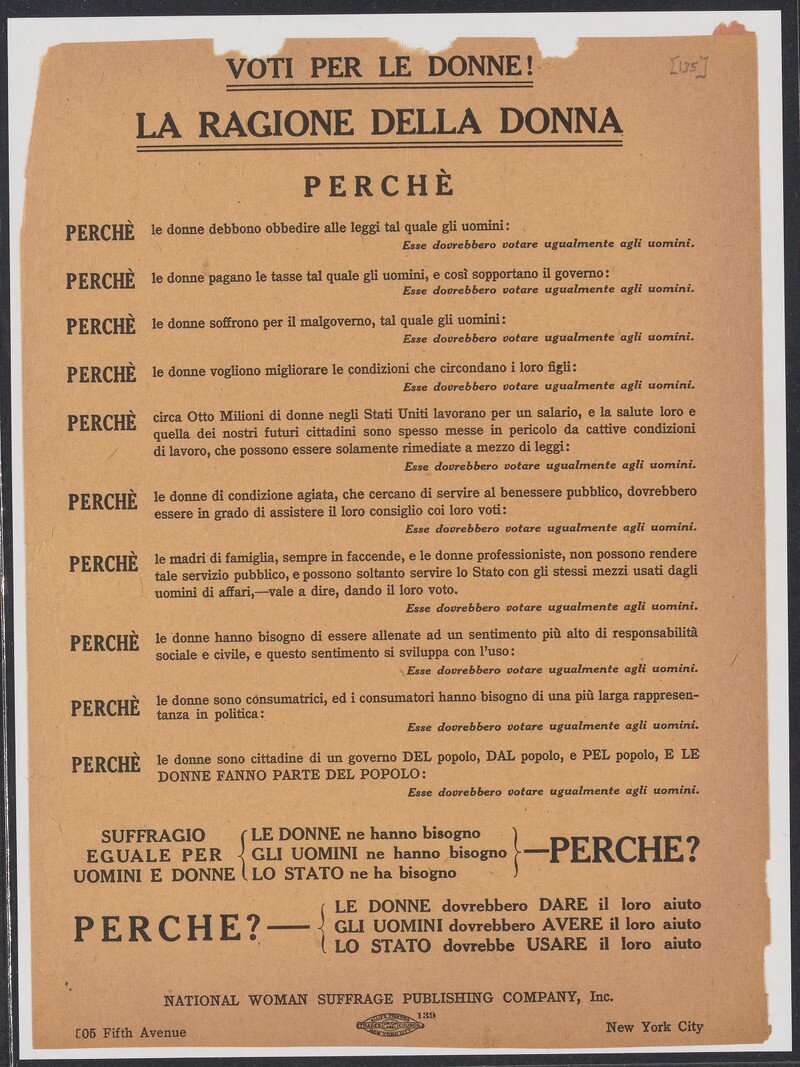

“PERCHE le donne sono cittadine di un governo DEL popolo, DAL popolo, e PEL popolo, E LE DONNE FANNO PARTE DEL POPOLO.” Women’s suffrage leaflet in Italian. Florence Luscomb Papers. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

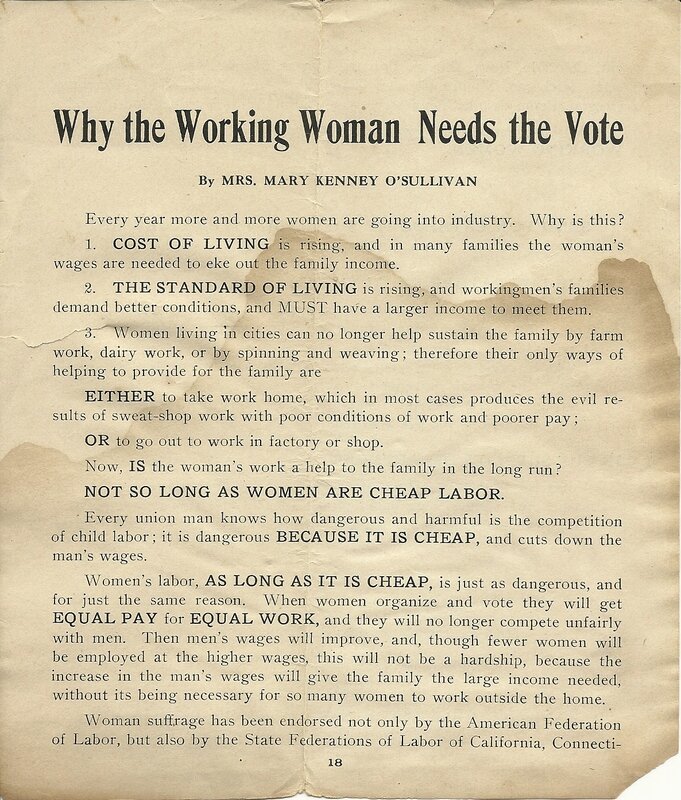

“A man and woman are working at the same piece of work, obtain the same results and spend an equal time on it, but when paying time comes, the woman’s salary is just half or one third of the man’s. Why? Because she is a woman and can’t help herself and he is a man and can vote.” — A Girl of 12 quoted in the Waltham Evening News, March 17, 1913.

Photo: Spinning Room, Cornell Mill, Fall River, Mass. by Lewis Hine, 1912. National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress.

“[In the] Evening Schools…. The chief subject of instruction is the English language, but some attention is given to civics, particularly for children of foreign birth.” —Margaret Hutton Abels, From School to Work, 1917.

DEMOCRACY

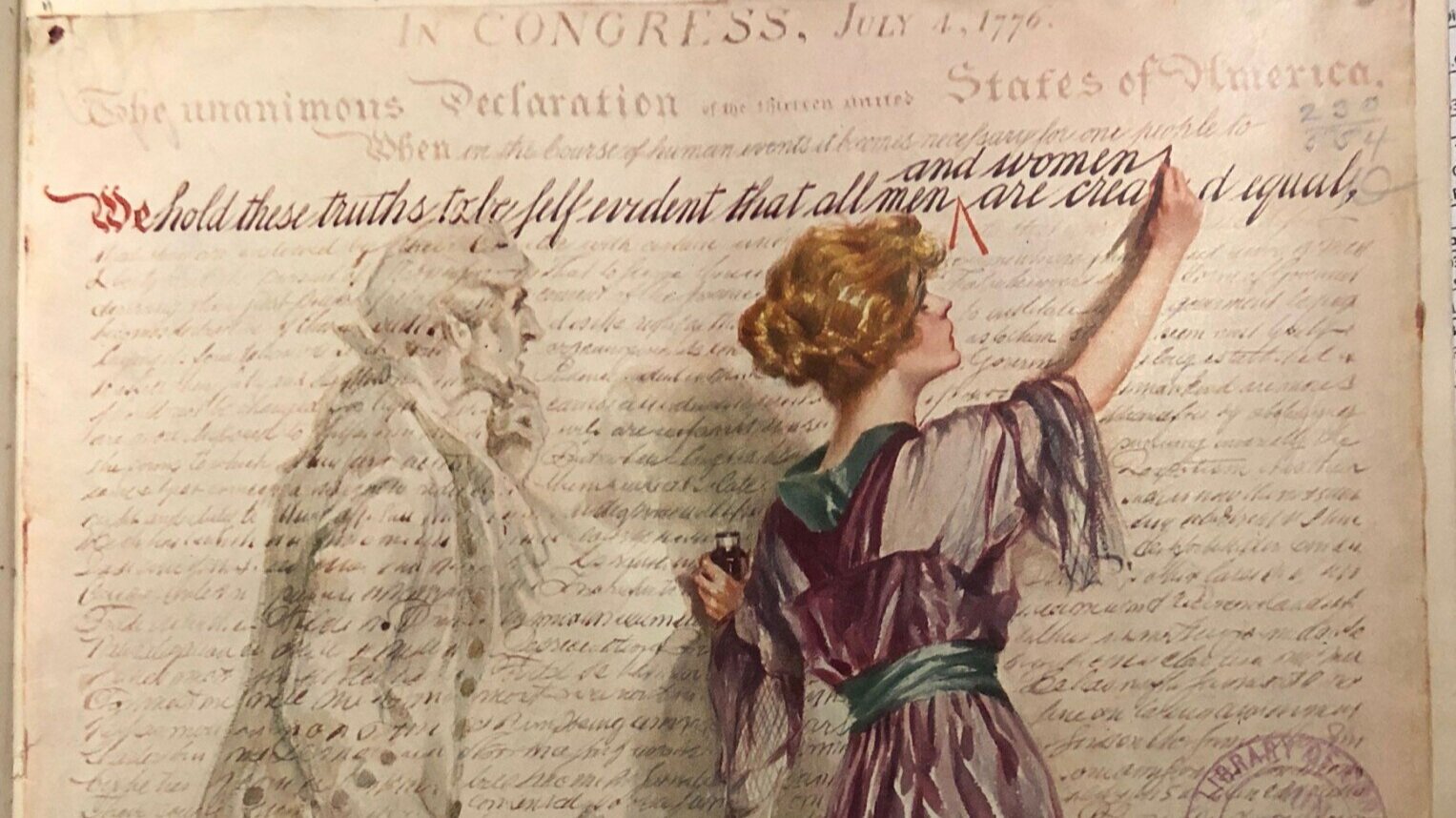

In civics class at school, students learn about rights and obligations of citizens. Often they see how the ideals of democracy do not line up with reality.

The great-great-grandfather of Ethel Paine of Waltham was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. She supported equal rights for women, workers and African-Americans. Library of Congress.

Waltham’s Emma Jennings, a formerly enslaved woman who worked for a family of suffragists, left no record of her own thoughts on voting rights. The Crisis, May 1916.

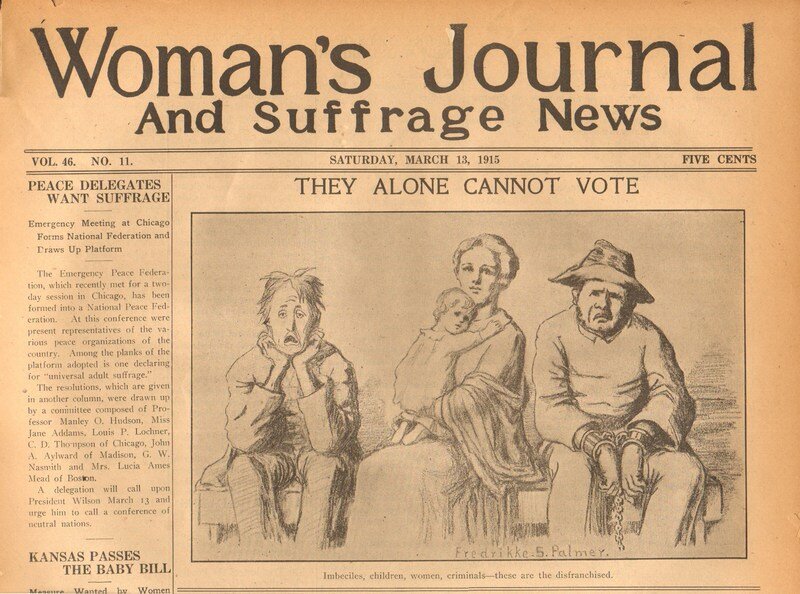

“They Alone Cannot Vote. Imbeciles, children, women, criminals. These are the disenfranchised.” — Women’s Journal, March 13, 1915. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

“A mass meeting 140 years ago had founded a great nation but had left great injustices and inequalities.” — Ida Hall (shown wearing a necktie). Boston Herald, April 17, 1901

PEACEFUL PROTEST

When people cannot access the ballot box, they find other ways to be heard. In the newspapers, on city streets, in hot air balloons and parade floats, activists raise their voices to fight for suffrage.

“Our leaflets are unpacked, our flag erected, we borrow a Moxie [soda] box…and proceed to the busiest corner of the town square. Our chief mounts the box, the banner over her shoulder and starts talking to the air…. Within ten minutes our audience has increased from twenty-five to five hundred.” Florence Luscomb, “Open Air Campaigning,” ca. 1909. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

“I had always thought that there were a few cranks pushing [women’s suffrage]. But that night I saw that it was earnest, intelligent, refined women, who had convictions and were not afraid to stand up and say so.” A Boston shopkeeper to Florence Luscomb, “Open Air Campaigning,” ca. 1909.

“At the outset, I decided to use no militant methods whatsoever.” — Margaret Foley, Boston Post, Oct 1, 1911.

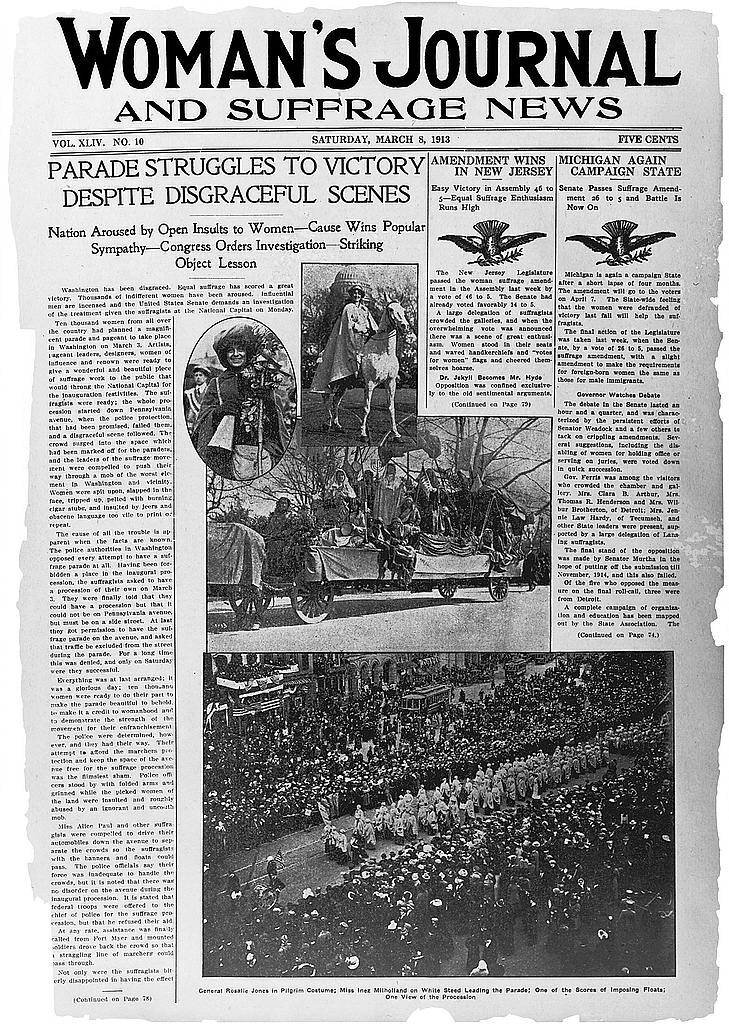

The mistreatment of parade marchers and their inadequate protection made newspaper headlines in every state. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

“[Parades] were some of the most effective bits of propaganda…. Just why seeing women walk down the street in parade should convince men to vote is a mystery, but it did so by the thousands.” —Florence Luscomb, Oral History, 1973. Photo: Waltham Historical Society.

“Everywhere we tacked up our “Votes for Women” bluebirds, occasionally stopping a farmer to ask him to assist us in wielding the hammer. I am sorry to relate that many a man seemed to have no knack in assisting.” Boston Globe, Aug 15, 1915.

Tin suffrage bluebird sign, 1915. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

“No state was ever carried for suffrage until it was sown ankle deep with leaflets” — Florence Luscomb. Image: Margaret Foley Collection, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

DEBATE

Outside of civics class, students see arguments for and against women’s rights in many forms of media.

Boston Globe, April 4, 1913.

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College.

Pro-suffrage women like Helen Keller and Robert Treat Paine’s daughter Ethel were dedicated pacifists. Woman’s Journal, May 16, 1896, p. 156. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

[1915-1917], Ann Lewis Women’s Suffrage Collection. From the collection of Ann Lewis and Mike Sponder.

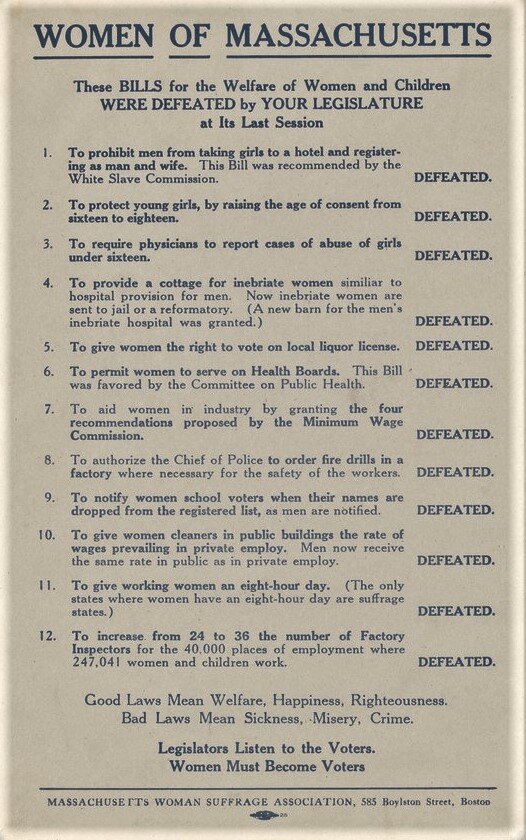

LEGISLATION

What does it take to change the law? Winning over public opinion is important, but not enough. Determined suffragists also fought a long legal battle for women’s voting rights.

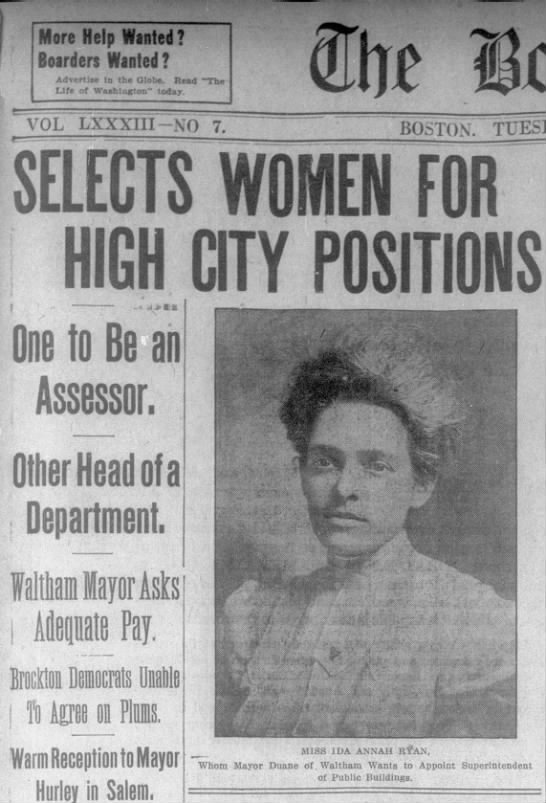

A local law in Waltham, Mass., stated that “the Inspector of Buildings and his assistants shall be competent men.”

The Boston Globe, Jan 7, 1913, p. 1.

“Legislators listen to voters. Women must become voters.” Leaflet drafted by Florence Luscomb, ca. 1912. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

Here, Florence Luscomb paints in Tennessee, the 36th and final state needed to pass the 19th Amendment. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Just a few years earlier, suffragists switched from the slow strategy of changing voting laws in every state to focus instead on changing federal law.

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Archives.

Banner image: Waltham Historical Society. Title image: Library of Congress.

“Anxious to Vote: Students, Workers and the Fight for Women’s Suffrage” is a curriculum and public education project developed in partnership by Stonehurst the Robert Treat Paine Estate and Waltham Public Schools in commemoration of the national suffrage centennial in 2020. STONEHURST is a National Historic Landmark owned by the City of Waltham. The once-private estate of generous social justice advocates whose ancestors helped establish the democratic foundations of this country is now appropriately owned by the people.

The Friends of Stonehurst received support for this program through “The Vote: A Statewide Conversation about Voting Rights,” a special initiative of Mass Humanities that includes organizations around the state. Our team includes Waltham History Department Chair Derek Vandegrift; Stonehurst Curator Ann Clifford; Kenneth Borter and the Waltham 8th-grade civics team; and consulting scholars Kathleen Banks Nutter, Barbara Berenson and Allison Horrocks.

This program is funded in part by Mass Humanities, which receives support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and is an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.